I usually stay pretty focused on my own navel here on the blog. I write about my own experience as a dad, and I don't usually spend a lot of time critiquing society or offering calls to action. And this post isn't intending to do those things, exactly, but I hope it offers something a little different to think about.

In May, I read a post from the National Fatherhood Initiative about a new program to help men in jail

reevaluate their responsibilities as fathers. And then the other day I learned that Sesame Street just created

a show for kids with parents in jail or prison. In the past, Sesame Street has tackled things like divorce and bullying, but this is a really significant new step. It's a thirty-minute special feature (you can watch clips of it

here) that probably won't be broadcast. With Father's Day around the corner, this stuff has got me thinking about parenthood and incarceration. One in 28 kids in the U.S. has a parent incarcerated. That's up from 1 in 125 twenty years ago. Where we'll be in twenty more years is anybody's guess.

This isn't a completely new thing for me; my wife actually spent most of her master's degree researching various angles on incarcerated men, especially their financial experiences. Several years back, we even moved to a town in Illinois and spent three months interviewing men in jail for her thesis. My thoughts stem from that experience.

_______________________

Across the table from me sat an imposing man - large in all directions. He wore a neatly trimmed beard, and smiled as all of the newly selected researchers took their seats. My wife and the other lead researchers had set up a preliminary discussion with this guy who'd recently been in the jail. He explained that, years before, he'd fled the state to avoid arrest for drug charges. He eventually joined a church, got married and had kids, and ended up deciding that he wanted to clean the slate. He returned to Illinois, walked into the jail, and asked to be booked so that he could serve his sentence. It wasn't easy. He lifted up his shirt and showed us the scars from improvised knives. He also described being allowed to hold private meetings in his room with several other men for what the guard thought were KKK meetings, though they were in fact scripture study sessions. If there's something I learned from that discussion, it was that appearances can be deceiving.

A week later, we arrived at the jail for our first visit. The female researchers had been asked, awkwardly, to please not dress provocatively. A guard took the entire team on a tour of the jail, and when we entered the cell blocks, every eye was on us. Men sidled up to the glass and leered. Some seemed to be goading others into calling things out. "Hey, sweet thing." "Hey, look over here." A couple men barked.

The first interview I helped run was with a young black guy, maybe 22 years old. He wore the standard black and white striped uniform. Scraggly beard hair. He sat comfortably, but with good posture. He gave us firm handshakes, and smiled. We asked him about his family relationships and about his children. We asked him what he was charged with. "Armed robbery," he said. What did he expect to do when he got out of jail, we asked. He wanted to be a chef, maybe start his own restaurant. When we asked how often he felt like he couldn't get going, he said, "every day."

How often did he feel depressed? "Every day." How often did he feel lonely? "Every day."

The next interviewee was easily six feet tall and 180 pounds of pure muscle. He entered the room cautiously, and his handshake was careful, tentative. We thanked him for coming in, and he waved it off, warming up to us. "Hey, I'm not doing anything else. And this research is gonna help people, right?" We said it was. "Well, let's get started!"

Another guy we interviewed sat across the table from us, fidgeting constantly. He cried after nearly every question we asked, and apologized each time. "I'm sorry guys, I don't know why I'm crying so much. I hardly cried at all last week." We asked if he had a good relationship with his parents, and he cried. We asked if he understood how compound interest worked, and he cried. He didn't know how it worked. The jail's nurse came in and gave the guy a paper cup with pills in it, and one filled with water. When she left, he explained,

"I've been in solitary for like three weeks now, and I swear I'm going crazy. I just needed to talk to someone."

We interviewed guys who were in jail on drug charges, for moving vehicle violations, for grand theft auto, for armed robbery and conspiracy to commit it, for murder, for sexual assault. One intimidating white guy, the minority race at this location, had a completely shaved head and extremely long goatee beard. He was covered in tattoos. It turned out his arrest was for dumpster diving.

We never knew whether many of the men had done what they were charged with. In fact, we told them it was in their best interest to merely state their charges, and not give further detail. Still, some frankly admitted guilt. Others admitted that they deserved to be in prison, but that the specific charges brought against them were bogus. Others said it was their first time, and they were scared. A few claimed innocence.

I'd always intellectually understood that guys who go to jail aren't necessarily bad people. But what struck me, over and over again, was how normal and friendly these men were. Once they were away from the watchful eyes of other men in the cell-block and alone with us in the interviewing room, they were just regular people. Yes, probably in many cases people who had made big mistakes. And there

were some men who refused to interview with us. But the ones who agreed seemed to genuinely want to both become better people, and to help other people to do the same. They shook our hands, laughed with us, told jokes, cried.

They talked about wanting to invest, wanting to hold a real job, wanting to provide for their wives, their girlfriends, their kids.

More than anything else, it was their kids who made them want to fix their lives. They didn't always know

how to fix things, but the desire was obvious. In talking with a lot of these guys, I couldn't help feeling that they were just like me, only they hadn't had all of my advantages. Many came from broken homes. Many lacked involved fathers; many learned to commit crimes

from their fathers. Many had never had a single male role model show by example that there were ways to survive without

resorting to crime.

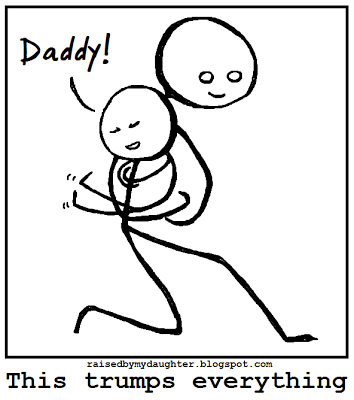

That's it. I don't have a huge point to make; mainly just that being a father

matters. Someday I want to do community service work in a jail; there's a demographic there that

needs people to care,

that needs people to try to understand. And it's a powerful thing to realize that fundamental feelings about parenthood unite us. For many of these men, fatherhood is a beacon of light, sometimes the only beacon of light, beckoning them in from the storm. And I salute any man who catches a glimpse of that beacon, and struggles forward against all odds to reach it. There's a lesson in that for all of us.